Regenerative Urbanism - Principle 4: Call forth a collective vocation

InsightsWhile Principle 3 is defined by the emergence of stakeholder groups and the process of self-organisation around a common place-based purpose that serves the greater good - Principle 4 focuses on the co-evolution of complex stakeholder systems, their adaptation, and ultimately their ability to flourish in the long term. This principle is a necessary component of delivering and stewarding long-term transformational change within cities and their communities.

How can we enable stakeholder groups to co-evolve and become resilient ecosystems in their own right? For system enablers, the key is to provide the conditions and support to ensure thriving communities that can self-actualise. Regenesis (2019) provides an example where species live in niches provided by other species - water and wind shape geology, create niches that invite life, shape their niches, and add to forms and flows.

To catalyse systems towards co-evolution, we must see people and nature as co-creators within the biosphere, regenerative regional economies, and culture.

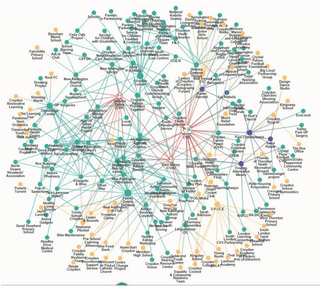

Asset Based Community Development (ABCD) Stakeholder Network - ©Kate White

Building Synergies within Business Guilds

Guilds are examples of complex reciprocity, in which exchanges are often indirect and equivalent value and impact is hard to measure. They apply to natural and human systems. Nature contributes to conditions that favour biodiversity and the health/evolution of the whole; the latter prospers where each stakeholder sees itself as invested in the whole.

Guilds form around organising cores, such as a vocation or place. Through a guild, partnership projects can leverage resources without adding expenditure (Regenesis et al., 2019).

Business guilds provide a community-scale example of interacting forms of capital and are a set of independent enterprises tied together by connections between some of their needs and yields. An example is Kalundborg Park, which shares resources and reuses surplus waste.

Guidelines for Applying the Principle

Regenesis, Many, and Haggard (2019) identify the following guidelines for the development of guilds:

Anchor thinking in the future - serves as a parameter for identifying guild members.

Start general, then go specific – consider different forms of capital as a tool to map stakeholders, then match capital with specific groups and individuals.

Map Relationships - as a web of relationships to map the guild - stakeholder relationships can also be anchored in place. Look to connect stakeholder groups to others in order to enhance the system.

Catalyse the Guild - which could include adding new resources, energy, and creativity to generate catalytic impact.

The Transformative Power of Social Innovation

Daniel Christian Wahl (2016) discusses the transformative power of social innovation. The Open Book of Social Innovation (Murray et al., 2010) offers an introduction to this broad field.

Collaborative Consumption

Collaborative consumption includes product service systems (PSS) where people can share products (car sharing), redistribution markets like eBay, and collaborative lifestyles where goods, time, skills, space, and money are exchanged throughout a community. According to Bostman and Rogers (2010), Digital platforms and real-time technologies are crucial for building trust between strangers, making these sharing economies possible on a large scale.

Case studies

The following case studies provide both international and UK examples of these principles in action, some of which exemplify our approach to evolving a stakeholder system.

PLANT CIC - NOMA, Manchester

In recent years, Plant CIC has engaged with thousands of people in Greater Manchester. Spending time in places gardening together has proven to be an invaluable way of building trust, community, and a deeper understanding of place.

Independent surveys commissioned by The National Trust have proven that Plant overwhelmingly increases participants' connection to place and can be instrumental in building community.

Interestingly, the urban activators involved within Plant CIC have evolved themselves to continue the development of stakeholder systems, some of which are in different places - for example, Joe Hartley created YellowHammer, a community bakery and pottery studio, forming a key part of Stockport's thriving creative and cultural Underbanks community ecosystem.

Community Urban Growing - Plant CIC

Time-Banking

Time-banking can help build mutually supportive neighbourhood-level support networks that are independent of market economies in a region. People organise themselves around a common purpose and exchange time rather than money - depositing hours in a time bank, which they are able to withdraw in terms of equivalent support when needed. This enables the growth of social cohesion and social capital.

Other examples include the metacurrency project Open Money and regional/local currency projects. Co-production aims to regrow and strengthen the social economy as a core sector and is central to all public services.

Wahl (2016) identifies that the fourth sector unites these activities - creating social, ecological, and economic benefits by using effective tools from the first (business for profit), addressing challenges from the second (government and administration), informed by social and environmental ethics of the third. It has emerged in the USA, Denmark, and the Basque country. In Majorca, The Business Alliance of Local Living Economics (BALLE) is a similar type of network, with an aim to strengthen local economics through supporting locally-owned independent businesses, thus creating the conditions for co-production to flourish and building resilient communities.

Participatory Urbanism

Most academics agree that participatory urbanism is a key part of regenerative practice.

Participatory Experimental Urbanism represents participation and 'commoning' - a practice of collaborating and sharing to meet everyday needs and achieve well-being for individuals, communities, and environments - through peer-to-peer platforms to redesign local economies.

Lambeth / Barking and Dagenham

In Lambeth, a partnership was struck between Lambeth Council and Civic Systems Lab for a new Open Works Project. A number of community projects were developed, utilising participation and open-source design-thinking with a view to catalysing the local economy.

It is distinct from traditional models of community volunteering and philanthropy that have kept economic impacts separate.

The aim is to facilitate ecologically sustainable, self-sufficient livelihoods based on interdependency and a circular economy - making, mending, recycling, cycling, pooling resources and learning, repairing rather than buying. Thus, communities become less dependent on the state and the market.

Following the completion of Open Works in 2015, and supported by funding, this model was pitched to London Borough of Barking and Dagenham, who were pivoting from the council as provider to facilitator and catalysing voluntary sector functions. What emerged was the participatory city programme, which was much grander in scale than Open Works. It was designed as a support platform - human, physical, and digital - for building new systems of production, consumption, distribution, and exchange based on local supply chains and circular principles.

The model has not been without tensions around certain participatory restrictions. As the model scaled, tensions occurred between programmed curation and open participation - decisions being made in an undemocratic forum.

Furthermore, while aiming to foster greater community engagement, the programme largely failed due to several factors, including: a top-down approach that was not flexible enough to accommodate diverse perspectives; a lack of focus on addressing residents' needs and concerns related to rising inequalities and poverty; and a failure to establish effective public accountability and community representation.

Open Works - © Laura Billings

Facilitating Systems Innovation and Culture Change at a Neighbourhood Scale

The 2009 Nobel Prize winner Elinor Ostrom investigated why large-scale, top-down delivery of public services is not as effective without direct community involvement compared to more participatory approaches based on human-scale collaboration between service providers and communities receiving those services.

Systemic change and renewed vibrancy happen when you ask people to use their skills to help provide services that are important to their communities.

"The people who are currently defined as users, clients or patients provide the vital ingredients which allow public service professionals to be effective. They are the basic building blocks of our missing neighbourhood-level support system - families and communities - which underpin economic activity as well as social development" (Boyle & Harris, 2009: 11).

Kelvin Campbell identifies neighbourhood management programmes that "draw together all service providers in a single and focussed approach, ensuring effective and scaleable neighbourhood infrastructure and services are delivered."

Examples include maximising community assets through local booking systems and coordinating procurement of goods and services in order to deliver good public outcomes. Other tools include community charters, local agreements, and new social contracts (Campbell, 2018).

The National Association of Neighbourhood Management points to residents working in partnership with mainstream service providers, the local authority, and businesses in the voluntary and community sectors to make local services more responsive to the needs of their area. It is a process that recognises the uniqueness of each place, along with the people that live, work, or provide services in it, to build on its strengths and address local challenges.

Understanding the uniqueness of a place and regional culture can unlock opportunities for transformative innovation and preservation of biological and cultural (biocultural) diversity, which includes indigenous local wisdom - working with unique and interconnected patterns of living networks. However, solutions to problems need to be supported by planning and governance structures.

Reforming Networks - GM's Approach to Community Deals

The application of stakeholder involvement in the delivery of services is being pioneered at levels of strategic governance across Greater Manchester. Wigan Council was known for its pioneering "Community Deal" approach, launched in 2014, which aimed to empower local communities and shift the focus of public services from traditional top-down delivery to a more collaborative and community-centred model. Key features included:

- Community Asset Transfer: The council promoted the transfer of public assets, such as community centres or green spaces, to local community groups and organisations. This allowed communities to take control of these assets and use them for the benefit of residents.

- A cooperative approach to service delivery, tailored towards citizens' specific needs.

- Health and Wellbeing Initiatives and Social Care Integration: The council collaborated with local health partners to promote community health and wellbeing initiatives. These efforts included programmes to encourage physical activity, combat social isolation, and improve mental health.

- Community Hubs: The establishment of community hubs served as focal points for local engagement, where residents could access a range of services and participate in community activities. Plant's work at Pennington Flash provides an example of a place-specific systemic intervention.

- Wigan Council's Community Deal approach has been successful, leading to significant budget savings, improved public health outcomes, and a cultural shift towards empowering residents and communities - saving over £141 million by February 2019.

Community Hub at Pennington Flash - Planit

Creating the Framework for Evolution of Stakeholder Systems

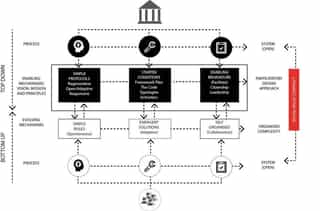

As Kelvin Campbell notes in his book "Massive Small Change," in order to enable evolution, designers should create a loose framework for it to occur. This can comprise:

- Simple protocols: Rules that guide complex choices and achieve solutions.

- Starter conditions: Principle-based conditions providing balanced constraints for emergence and innovation.

- Enabling behaviours: Appropriate forms of leadership, management, and ethics governing behaviour.

His framework is based on the four key principles of designing for co-evolution:

- Focus on Social Flows and Exchange

- Utilise Community Design Intelligence

- Stimulate Collaborative Frameworks

- Design for Value Generation

The framework should also include a collaborative approach to adding value through interdependence.

Campbell identifies that successful systemic change requires an intimate understanding of the human side, as well as the overarching culture, values, people, and behaviours that must change to deliver the desired results.

Peter Senge in his book 'The Fifth Discipline' envisions a learning organisation as a group of people who are continually enhancing their capabilities to create.

Leaders need to think less like managers and more like biologists, growing rather than changing; something new grows and supplants the old, rendering it obsolete.

Flexible Frameworks for Delivery. Reinterpretation of Kelvin Campbell's Massive Small Change Framework - Planit

Tools

Appreciative Inquiry (AI)

There are various tools and techniques that could be utilised to support the co-evolution of stakeholder systems.

Appreciative Inquiry (AI) is action-based research developed by David Cooperrider and Suresh Srivastva to build shared visions. They felt that the problem-solving approach hampered social improvement.

Appreciative Inquiry engagements are designed and delivered using the 5-D process consisting of:

- DEFINE: Choose the affirmative topic or focus for the inquiry.

- DISCOVER: Inquire into positive moments and share stories.

- DREAM: Create inspiring images of a desired future.

- DESIGN: Innovate ways to create the ideal future.

- DESTINY: Live your design and make changes as needed.

Appreciative Inquiry (AI) supports the co-evolution of stakeholder systems by fostering shared positive visions, promoting collaboration, and building collective ownership through a strength-based inquiry process. By focusing on past successes and peak experiences, AI helps diverse stakeholders discover common ground, develop innovative solutions, and create sustainable, positive change aligned with a shared future.

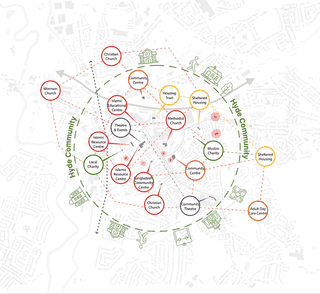

Ecosystem Mapping

Ecosystem mapping effectively maps out the dynamics of a stakeholder system in diagrammatic form, with different groups and their internal and external relationships, to identify issues and opportunities to enhance the connectivity, wellbeing, and effectiveness of the system.

Ecosystem mapping can be used to identify relationships between stakeholder systems and physical assets that exist within a place, e.g., Community Hall, Church, Park, Bowling Club, etc.

You can then find leverage points in the system to enhance the quality and connectivity of the relationships between groups and places, developing and enhancing a sense of belonging and active participation in achieving flourishing futures for places, their communities, and nature.

Mapping Stakeholder Networks with Place, Hyde Town Centre - Planit

Conclusion

The transition from traditional top-down governance to co-evolutionary stakeholder systems represents a fundamental shift in how we approach urban transformation. This principle recognises that sustainable change cannot be imposed from above but must emerge from the dynamic interplay between diverse stakeholders, their environments, and the places they inhabit.

The evidence presented - from Wigan Council's £141 million savings through community asset transfer to Plant CIC's demonstrated capacity to strengthen community connections -shows that co-evolutionary approaches deliver both social and economic value. These examples reveal a critical insight: when stakeholders become co-creators rather than passive recipients, they generate innovative solutions that formal institutions alone cannot achieve.

However, success requires more than good intentions. The failure of Barking and Dagenham's participatory city programme illustrates the risks of scaling without authentic community engagement. True co-evolution demands that power structures adapt alongside community capacity, creating governance frameworks flexible enough to accommodate emergent solutions while maintaining democratic accountability.

The tools and frameworks outlined - from Business Guilds to Ecosystem Mapping - provide practical pathways for city leaders. Yet their effectiveness depends on a deeper shift in mindset: from managing change to growing it, from solving problems to nurturing conditions where solutions can emerge organically.

Ultimately, enabling co-evolution is not just about improving service delivery or community engagement - it is about building the adaptive capacity necessary for cities and communities to thrive in an uncertain future.

The question for practitioners is not whether to embrace this approach, but how quickly they can begin creating the conditions for stakeholder systems to flourish.

Evolving Stakeholder Networks - Ancoats Green. Friends of Ancoats Green have taken on stewardship programmes associated with the new Neighbourhood Park - Planit

Related Thoughts

Regenerative Urbanism - Principle 1: Designing for co-evolution

Regenerative Urbanism - Principle 1: Designing for co-evolution

Regenerative Urbanism - Principle 2: Partner with Place

Regenerative Urbanism - Principle 2: Partner with Place

Regenerative Urbanism - Principle 3: Call forth a collective vocation