Designing as Part of a Living Network

InsightsPrinciple 5 from the 10 Principles of Urbanism. As part of my previous post on the 10 principles of Regenerative Urbanism, this article deep dives into the fifth principle: design as part of a living network.

The challenge

Our cities are disconnected from the living systems that sustain them. Despite growing awareness of climate breakdown and ecological collapse, most development still treats nature as a separate, external layer.

The result? Green spaces that get cut first when budgets tighten. Infrastructure that creates more problems than it solves. Communities disconnected from nature and each other, reinforcing a mindset that perceives us as separate from the living world and in turn degenerative and exploitive behaviour.

But there is another way

Following earlier reflections on the principles of Regenerative Urbanism, this article explores Principle 5: Design as Part of a Living Network. This principle recognises cities not as static artefacts or collections of projects, but as dynamic socio ecological systems shaped by flows of energy, materials, water, biodiversity, people and information. Designing within such systems demands a shift away from isolated interventions towards approaches that actively work with interdependence, feedback, diversity and continual adaptation over time.

Rather than positioning nature as an aesthetic layer or a compensatory mechanism, Principle 5 reframes ecological systems as foundational infrastructure. It asks how urban environments might be conceived, delivered and governed so that they behave more like living systems - capable of self renewal, learning and supporting long term human and environmental wellbeing.

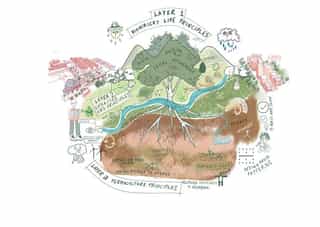

A Simple Framework: Three Lenses, One Goal

This article presents a practical way to design cities as living systems by combining three complementary approaches:

- Biomimicry Life's Principles → How does nature work?

The ecological logic: 3.8 billion years of strategies that create conditions for life - Nature-Based Solutions → What should we do?

Translating nature's logic into green interventions - Permaculture Principles → How do we do it?

The framework can be used as a thinking tool to ensure day-to-day decisions make regenerative design real.

Think of these as a flow: biomimicry provides the deep logic,

NbS translates it into design guidance, and permaculture makes it actionable.

Through analysis of three diverse case studies (Oldham Town Centre, Godley Green Garden Village, and Victoria North), we demonstrate how this framework reveals both achievements and opportunities, offering practitioners a methodology for moving beyond current practice towards a more living-systems approach to design.

The Three Approaches Explained

Biomimicry: Learning from 3.8 Billion Years of R&D

Nature has already solved most of the problems we face. Biomimicry asks: "How would nature design this?"

The Biomimicry Life’s Principles are a set of strategies that all organisms and ecosystems on Earth use for creating conditions conducive to life.

The theory is that by incorporating these principles into our design methodology, the resulting integrated strategies will be inherently sustainable because they follow the same principles that allow life to thrive:

Living systems follow patterns that enable them to survive and thrive. Biomimicry life principles include:

- Evolve through testing and learning

- Adapt to changing conditions

- Be locally attuned to place

- Use life-friendly chemistry (no toxins)

- Be resource efficient (nothing wasted)

- Integrate growth with development

Example in practice: Instead of concrete channels that flush rainwater away, create wetlands that clean water, provide habitat, and recharge groundwater - just like natural floodplains do.

Nature-Based Solutions: Design Interventions That Works Like Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines NbS as "any actions that protect, sustainably manage, or restore natural and modified ecosystems to address societal challenges" (Learn Biomimicry, 2025).

In their 2023 paper How Would Nature Design and Implement Nature-Based Solutions?, Bianciardi, Becattini, and Cascini translate the Biomimicry Life's Principles into a set of Nature-Based Solution design guidelines. These "extracted principles" sit between ecological strategy and design practice: they identify what good NbS must do in order to behave like living systems.

The extracted principles include:

- Diversity and Redundancy → Multiple species,

multiple solutions, backup systems - Self-Renewal → Systems that get better over time through feedback

- Local Attunement → Designed for this specific soil, climate, community

- Circular Flows → Water, materials, energy cycle rather than flow through

- Low-Impact Operations → Minimal energy, no toxins, passive systems

- Modular and Nested → Small parts work independently and together

- Cooperation → Multi-stakeholder, mutual benefits, ecological partnerships

Example in practice: A town centre park that harvests rainwater (circular flow), includes native species along with non-native where longer term climatic adaptation needs to be considered (local attunement), provides multiple community benefits (cooperation), and evolves through community stewardship (self-renewal).

Permaculture: Design Principles for Human Systems

The twelve permaculture design principles, articulated by David Holmgren, are:

- Observe and Interact - Spend time understanding before acting

- Catch and Store Energy - Capture resources when abundant

- Obtain a Yield - Ensure practical, measurable benefits

- Apply Self-Regulation and Accept Feedback - Learn and adapt continuously

- Use and Value Renewable Resources and Services

- Prioritise regenerative over extractive - Produce No Waste - Everything is a resource for something

- Design from Patterns to Details - Understand the big picture first

- Integrate Rather than Segregate - Create beneficial relationships

- Use Small and Slow Solutions - Value appropriate scale and pace

- Use and Value Diversity - Diversity creates resilience

- Use Edges and Value the Marginal - The most productive zones

are often transitional - Creatively Use and Respond to Change - Design for change

rather than against it

These principles are grounded in three core ethics: Earth Care, People Care, and Fair Share. They are seen as universal thinking tools that, when used together, allow us to creatively redesign our environment and behaviour in a world of declining energy and resources.

Case Studies

Nature-Based Solutions in Practice

The following three case studies provide a range of examples from which to assess the nested framework.

Their unique propositions include:

- Oldham Town Centre:

Integrating green infrastructure as a catalyst for urban regeneration - Godley Green Garden Village:

A new urban settlement that connects living neighbourhoods to nature - Victoria North:

A new city neighbourhood of 15,000-20,000 homes integrated within an existing landscape valley, utilising Natural Capital Accounting within the masterplanning process

Each project is presented through four lenses: context and challenge, design response, framework alignment, and opportunities for deepening regenerative practice.

↑ Eco Streets, Oldham - Integrating Rain Gardens

Case Study 1: Oldham Town Centre

Context and Challenge

Oldham Town Centre faced entrenched social inequalities, poor pedestrian connectivity, vehicle-dominated streets, and limited access to green space. The town centre had become disconnected from its communities and was experiencing economic decline alongside environmental degradation and flood risk.

On the back of £3 million of United Utilities funding-proposed as an alternative to large capital investment in hard infrastructure to reduce flooding and improve water quality within the catchment area - a cocktail of additional funding was secured to create a framework for significant physical, economic, and social change. This included Growth Deal 3, the Mayor's Walking and Cycling Fund, Future High Streets Fund, UK Shared Prosperity Fund, Levelling Up Fund, UU Green Recovery Fund, Town Fund, Brownfield Fund, and City Region Sustainable Transport Settlement.

Key Innovation: Material Reuse

In a UK first, the surface of existing stone setts was relaid to a new pattern and then ground down to reveal a new wearing course, which was then relaid into a new design. A successful trial took place on site where different methods were reviewed. This innovation created significant environmental benefits over sourcing new materials. Additionally, it allowed the allocated budget to stretch further and contribute toward bespoke integrated furniture items and large mature trees.

The project created a 'regenerative ripple effect' in that by providing a novel solution that worked, this enabled replication across other sites (Planit have replicated on other schemes such as Liverpool Waters), saving materials from waste and unlocking broader environmental impact.

Green Streets

The project introduced Green Streets including several targeted streetscape green infrastructure improvements across Albion Street, Henshaw Street, Union Street, and Yorkshire Street:

- Soft landscaping with tree planting and low-lying greenery, harvesting rainwater to mitigate flooding

- Multi-purpose green structures with green roofs, integrated lighting, seating areas, and adaptability for market stalls

- Green walls, planters, and hanging baskets near high street shops to enhance urban ambiance and support environmental quality

- Rainwater harvesting in soft-landscaped areas to boost environmental sustainability and resilience

- Seating allowing residents and visitors to enjoy green outdoor space for socialising, supporting mental and social wellbeing

↑ New Town Park - Breathing life back into Oldham Town Centre

The New Town Centre Park

A significant opportunity arose to create a major new public park occupying two brownfield sites formerly housing the market (relocated into Spindles Shopping Centre) and the Leisure Centre (moved to a new location west of the town centre).

Inspired by Parisian parks, the scheme delivers a diverse range of uses with underpinning themes of biodiversity and management of both extreme rainfall and temperature events in line with latest climate change predictions.

The park aims to improve quality of life for nearby residents and create a place where people want to live. The linear park is expected to encourage outside investment to develop adjacent plots of land for new residential developments, creating a critical mass of people to help town centre businesses thrive and allow Oldham to develop its evening economy.

Park Features:

- Retained existing trees and planted 85 new trees

- Woodland glade planting, heather terraces, lawns, and gravel paths

- Central lawn and children's play area

- Picnic benches and illuminated pathways for safety

- Cycle lanes connecting to wider routes

- Formal gardens and bodies of water

- Sports and play facilities

- Open green space for events

- Bouldering walls and BMX pump track

- High-quality pedestrian and cycle linkages

These features create a vibrant green corridor that enhances biodiversity, improves pedestrian and cycling connectivity, and provides community space conducive to relaxation and active lifestyles.

↑ New Town Park - Provides the catalyst for a new town centre residential neighbourhood - generating gentle and liveable densities

What Works Well

Oldham demonstrates how nature-based interventions can address entrenched social inequalities while reshaping the urban environment as a healthier, greener, and more adaptive system.

- Multiple functions: flood management + biodiversity

+ community space + active travel. - Material reuse innovation saves carbon and money.

- Green infrastructure connects to social regeneration.

- Rainwater harvesting creates circular water flows, considering climate change and incorporating climate adaptive design solutions to ensure longevity.

Opportunities

When viewed through the biomimicry lens of diversity, redundancy, and adaptive feedback, new possibilities emerge. Oldham's nature-based assets are effective but relatively centralised - albeit slowing water at source being a key principle of United Utilities' investment. Small-scale ecological niches and micro-infrastructures are less prevalent.

- More small-scale interventions (pocket meadows, alleyway greening).

- Community monitoring and feedback systems.

- Stronger connections to surrounding landscapes.

- Integrate rather than segregate solutions - hydrology and biodiversity.

Framework Alignment

- Biomimicry: Locally attuned (responds to flooding and social needs);

resource efficient (material reuse). - NbS: Cooperative relationships (multi-stakeholder funding);

cyclic flows (water harvesting). - Permaculture: Produce no waste (setts reuse); integrate rather than segregate (GI throughout civic realm)

- effective and appropriate management/stewardship to allow life to flourish.

↑ Godley Green Masterplan - integrating the neighbourhoods into the Pennine Landscape

Case Study 2: Godley Green Garden Village, Hyde

Context and Challenge

Godley Green in Tameside presents a unique opportunity to apply the framework prospectively - embedding regenerative principles from planning rather than retrofitting later. This proposed Garden Village of up to 2,150 homes across 150 hectares in the Peak District foothills represents a chance to create a 21st-century community that gives back to existing settlements (Hattersley and Hyde) and the natural landscape.

The site consists of intensively farmed fields with impoverished soils, existing woodland including ancient woodland fragments, watercourses, and significant hillside topography. The challenge: restore ecological function while providing high-quality housing with community stewardship embedded from day one.

Design Response : Landscape-Led Garden Village Principles

Planit produced a Green and Blue Infrastructure Strategy and GI Design Code to support the submission of an outline application, creating the framework for a regenerative approach to landscape and green infrastructure delivery.

The landscape-led development includes creation of a network of green and blue infrastructure, including a new 100-hectare Countryside Park.

The masterplan establishes two connected villages with distinct identities, each served by local hubs offering flexible workspace, community facilities, retail, cultural and leisure uses.

Seven Core Objectives

- Beyond the Garden City Brand - Garden City principles enshrined throughout from masterplan to long-term stewardship, designing with existing communities fundamentally.

- Two Villages that Give Back - Actively contributing to Hattersley and Hyde through employment, education, training. Developer contributions improve local infrastructure.

- Smart, Resilient, Zero-Carbon Energy - Energy efficient and climate-resilient development addressing Greater Manchester's Net Zero 2038 targets.

- High-Quality, Sustainable Homes - Locally distinctive, truly sustainable architecture respecting surrounding landscape.

Higher density around Hattersley Station and village hubs. Range of types and tenures meeting local needs. - Enhance Nature and Biodiversity - Preserve and enhance Sites of Biological Importance (Werneth Brook, Brookfold Wood), ancient woodland, watercourses, ponds. Integrate nature into overall place structure, connecting homes and nature visually and physically.

- Green Streets and Spaces - Extensive GI including large-scale street tree planting. Public realm designed to encourage food production at all scales from streets to communal allotments.

- Bikes and People over Cars - Priority to cycling, walking, public transport. Clear network of attractive streets, footpaths, cycleways. Trans Pennine Trail incorporated and enhanced.

The Funding Gap

Annual revenue potential (£605,495 from ground rent, events, cafés) versus costs (£675,000) creates circa £70,000 shortfall before additional unaccounted costs. This demands flexible, innovative approaches drawing on diverse funding streams and multiple partners. As a consequence, different models were explored through the Outline Planning Application: developer-led, transfer to a charitable trust and a hybrid partnership.

↑ Connecting housing to the semi-natural landscape

What Works

Godley Green demonstrates sophisticated prospective application of the framework:

- Stewardship embedded from planning stage, not retrofitted

- Community Activator role addresses common failure - absence of funded community development capacity

- Multiple funding streams identified beyond contentious ground rent

- Explicit recognition of low-carbon trade-offs

(different aesthetics, maintenance requirements) - Food production integrated at all scales creating productive landscapes

- Two-village structure with distinct identities supports diverse community scales

Opportunities

- Translating principles into robust planning conditions that survive delivery

- Securing endowments and alternative revenue sources through planning obligations

- Community Activator engaging existing residents while creating frameworks for future residents

- Net Zero commitment translated into specific standards,

specifications, strategies - Strong masterplan controls maintaining landscape-led vision

across phased delivery - Risk aspirational language doesn't survive value engineering

Framework Alignment

- Biomimicry: Evolve to survive (stewardship must adapt and learn); locally attuned (Peak District character, Sites of Biological Importance); integrate development with growth (phased approach, community develops alongside physical development)

- NbS: Cooperative relationships (multi-stakeholder models); diversity and redundancy (varied open space types, flexible funding streams); self-renewal (Community Activator, adaptive governance); modular and nested (two-village structure); local attunement (preserving existing natural features)

- Permaculture: Observe and interact (detailed landscape analysis before intervention); design from patterns (landscape-led masterplan); integrate rather than segregate (homes and nature connected visually/physically); obtain a yield (gives back to existing communities, food production); apply self-regulation (adaptive governance from start)

Case Study 3: Victoria North, Manchester

Context and Challenge

Victoria North represents an unprecedented scale of regeneration in Manchester, revitalising existing communities and forming a catalyst for growth within the northern edge of the city. The site is equivalent to nearly a third of the size of the extended city centre and represents Manchester's single largest and most ambitious development opportunity.

Established through a Strategic Regeneration Framework (SRF) adopted in February 2019, the regeneration of the Lower Irk Valley into Manchester's City River Park forms the binding agent of Victoria North - a series of mixed-use neighbourhoods comprising 15,000-20,000 homes.

Victoria North represents the single largest opportunity to deliver on Manchester's ambitious carbon reduction targets of Net Zero by 2038 and to act as a driver for positive change and inclusive growth. The requirement to provide a social and environmental legacy has driven the design and stewardship model for the City River Park and all partners involved.

Design Response

Hydrology

The project leverages the Irk Valley's hydrology and woodland landscape as the central organising principle of the regeneration framework. The river corridor becomes both ecological infrastructure and community connector, structuring the development around natural systems rather than imposing development first and retrofitting green space

Natural Capital Accounting

One of the key innovations at Victoria North was the application of Natural Capital Accounting within the masterplanning process, conducted through a series of workshops with Vivid Economics.

Key Lessons Learned

The team had to determine specifically what questions they wanted to answer -what opportunities and value they wanted to define through natural capital accounting - and what data they had available.

Due to the relatively small scale of the Victoria North site compared to UK-wide datasets that the natural capital account was based on, the results were limited. It was difficult to establish specific value for small green spaces. The team had good overall figures to report but they were catchment-wide rather than site-specific.

The broad range of topics and use of UK-wide datasets meant the Ecosystem Service Opportunity mapping could be misleading or incorrect when looking at a small area.

Important Finding

There was a significant difference in ecosystem opportunity potential dependent on the location and urban characteristics of each area - some comprising former heavy industry while others being Urban Fringe/River Valley Landscape. Typically, there was high demand for natural capital in densely populated urban areas.

Low-Carbon Design Approach

In direct response to the declared Manchester Climate Emergency, combined with a desire for no further financial burden on the public purse, low-carbon solutions to landscape treatments and ongoing stewardship lie at the heart of City River Park design, providing opportunities for carbon sequestration

Following adoption of the SRF, the vision developed around a high-level guide and analysis on embodied carbon within the seven linked parks and how a low-carbon approach to design and specification might be employed to focus on climate adaptation and address the commitment to Net Zero.

↑ Angel Meadows - Green Infrastructure acts as a bridge between historical and new fabric and as a foil for living streets

What Works Well

Victoria North delivers strongly against NbS principles related to resilience, scale, and cooperative relationships.

- Hydrological system as organising principle

- Catchment-scale thinking beyond site boundaries

- Gap analysis prioritises areas of greatest need

- Climate commitments embedded from the start

Opportunities

Biomimicry elevates several important insights for Victoria North. Living systems distribute risk through decentralisation and nested modularity-principles that can be further leveraged here.

- More small-scale neighbourhood interventions (micro-wetlands, pocket parks)

- Community monitoring and citizen science

- Productive edges (riverbanks, brownfield fragments)

- Stronger material cycling (compost systems, circular construction)

- Building ecosystem enhancement into construction contracts

- Transition of strategy goals into development projects - early phases have failed to reach the ambitions around nature recovery and flooding

- Better understanding of the baseline - particularly in relation to historic ground contamination

Framework Alignment

- Biomimicry:

Locally attuned (catchment-wide); resource efficient (low-carbon design) - NbS:

Modular and nested (seven linked parks); cooperative relationships (multi-agency governance) - Permaculture:

Design from patterns (river as structure); use edges (valley as productive zone)

Cross-Project Analysis

Five patterns of Success

Applying the nested framework across the three case studies reveals common regenerative patterns and collective insights that transcend individual project contexts.

1. Let Ecology Lead

What this means: Green infrastructure organises development, not the other way around.

Standard practice

Place buildings first, fit green space into leftovers.

Regenerative practice

Understand ecological systems first, design development to work with them.

- Godley Green: Landscape-led Garden Village principles structure two villages around Peak District features

- Victoria North: River valley organises neighbourhoods

- Oldham: Green network catalyses town centre transformation

Why it matters

When ecology leads, green infrastructure creates structure to places. It can perform multiple functions and operate at landscape scale.

2: Many Small Things > Few Big Things

What this means

Resilience comes from diversity and redundancy - lots of small systems backing each other up.

All three projects could benefit from adding:

- Smaller-scale interventions complementing large gestures

- Functional redundancy (backup systems)

- Modular components that can evolve independently

- Edge conditions and transitional zones

Why it matters

If one system fails, others continue working. Small interventions reach more people, adapt faster, and build ecological density.

3. Build in Feedback Loops

What this means

Living systems sense and respond. Places should too.

What's needed

Community monitoring (biodiversity, water quality, social use)

Regular review processes

Simple sensing (soil health, plant growth)

Adaptive management protocols

Citizen science programs

Why it matters: Without feedback, even great designs become static.

With it, they evolve and improve.

4. Close the Loops

What this means

Outputs should become inputs - water, materials, energy, nutrients cycling not flowing through.

Current state

- Oldham: Water harvesting ✓, Material reuse ✓

- Godley Green: Food production at all scales ✓, Traditional management ✓

- Victoria North: Low-carbon materials ✓

Opportunities everywhere

- Composting systems turning "waste" into soil

- Timber from park management used in construction

- Rainwater feeding landscape irrigation

- Food production in public spaces

- Renewable energy from organic materials

Why it matters

Circular flows make systems self-renewing and reduce external dependency.

5. Govern Like Ecosystems

What this means

Multiple actors creating mutual benefits through cooperation.

All three projects demonstrate different partnership approaches:

- Oldham's creative funding assembly

- Victoria North's multi-agency framework

- Godley Green's explicit exploration of three stewardship models

Godley Green's detailed stewardship analysis reveals how critical governance structures are. The Community Activator role-bringing together stakeholders, facilitating community projects, building stewardship capacity before communities exist-addresses common failures in new developments.

Ecosystems work through mutualism - bees get nectar, flowers get pollination. Urban projects should too:

Multi-stakeholder partnerships

- Community stewardship models

- Long-term management commitments

- Shared decision-making

- Adaptive governance structures

Why it matters

When many parties have stake and agency, systems can evolve beyond any single organisation's limitations. Capital funding for creating GI is often available; ongoing maintenance funding is scarce. Community stewardship, cooperative governance, social enterprise approaches bridge this gap.

↑ Evolving Stakeholder Networks - Ancoats Green - Friends of Ancoats Green have taken on stewardship programmes associated with the new Neighbourhood Park - Planit

How to Use This Framework

A framework is only useful if it provides clear criteria for evaluation. The nested Biomimicry-NbS-Permaculture approach offers multiple lenses for measuring regenerative performance.

For Project Teams

Phase 1: Observe and Analyse

- Conduct ecological baseline assessment (current and historical)

- Map social-ecological systems and relationships

- Identify ecosystem service opportunities and gaps

- Analyse soils, ground conditions, material, water, and energy flows - particularly historic flows

- Assess governance structures and stakeholder relationships

Phase 2: Design with the Framework

- Check against Biomimicry Life's Principles: Does your design create conditions conducive to life? Does it evolve, adapt, use resources efficiently, integrate development with growth?

- Apply NbS Criteria: Does it provide diversity and redundancy? Is it locally attuned? Does it create cyclic flows and cooperative relationships?

- Operationalise with Permaculture: Are you observing first? Integrating rather than segregating? Using edges? Obtaining yields while caring for earth and people?

Phase 3: Iterate and Adapt

- Establish feedback mechanisms from the start

- Create adaptive management protocols

- Build community stewardship structures

- Monitor ecological and social metrics

- Adjust based on learning

For Different Audiences

Policymakers

- Mandate ecosystem function measures, not just green space area

- Require natural capital accounting in feasibility studies

- Fund long-term stewardship, not just capital delivery

- Create adaptive management requirements

Communities

- Demand regenerative approaches in local development

- Establish stewardship programs

- Monitor ecological and social performance

- Create cooperative governance

- Ensure local community groups are motivated but also ensure backup systems of cooperative stewardship so minimal levels are always maintained

What's Stopping Us?

If this works so well, why isn't everyone doing it?

Structural Barriers

- Procurement designed for linear infrastructure

- Planning policies that measure area, not function

- Economic models that don't value ecosystem services

- Short-term political and funding cycles

- ace of investment and development - doesn't support 'use small and slow solutions' principle

- Siloed professional disciplines

The Reality

These projects succeed despite the system, not because of it. They required exceptional effort, champion clients, and creative funding assembly.

What's Needed

- Policy reform mandating regenerative approaches

- Economic valuation of natural capital

- Long-term funding for stewardship

- Cross-sector collaboration requirements

- Education systems teaching systems thinking

The Path Forward

Change is coming from two directions:

Top-Down

- Policy frameworks that mandate ecological integration, reward regenerative innovation, and value natural capital.

Bottom-Up

- Community-led climate action, urban food networks, cooperative stewardship, and local nature recovery showing what's possible.

- Ensuring local community groups are motivated is key but also ensuring backup systems of co-operative stewardship so that minimal levels are always maintained.

The Transformation Happens When These Meet

Bottom-up innovation proves what works. Top-down reform enables it at scale. Communities demand it. Practitioners deliver it. Policy enables it.

Conclusion

The living networks our cities need will not emerge from just more parks, greener roofs and smarter technology.

They will emerge from the addition of better relationships:

- Between people and nature

- Between scales of intervention

- Between infrastructure systems

- Between the disciplines shaping our future

Oldham, Godley Green, and Victoria North show this is possible. Applying the framework demonstrates that when we design with ecological structure leading, create diverse distributed systems, build in feedback, close resource loops, and govern cooperatively, cities can function as living networks.

The work begins with the next project.

Not with grand strategies or perfect policies, but with practitioners using this framework to ask better questions, make better decisions, and build projects that create conditions for life.

Three questions to start:

- What ecological systems could organise this project?

- How can we build diversity, feedback, and circularity?

- Who needs to cooperate for this to evolve over time?

Answer these well, and you're designing as part of a living system.

Related Thoughts

Regenerative Urbanism - Principle 4: Call forth a collective vocation

Regenerative Urbanism - Principle 4: Call forth a collective vocation

Regenerative Urbanism - Principle 3: Call forth a collective vocation